Apple's AI Personalization

Proactive vs. Reactive

A proactive app 1) considers information it knows about you, 2) unearths certain patterns of your behavior, and 3) provides useful suggestions and personalizations accordingly.

The most impactful consumer AI use cases have not been proactive but reactive ones, where users explicitly state what they are trying to do and the AI executes the necessary actions to complete it.

For example, users can select a text on an iPhone and use the writing assistant tool to proofread or change the tone. For more advanced use cases like in Gemini Live, users make a request to send the directions to the nearest greek restaurant to a friend via a text message.

Through this process, the system may capture user preferences, such as a tendency to edit business-related emails more frequently than personal ones, a preference to eat at Evvia for lunch meetings, or the frequent usage of WhatsApp over Messenger. However, we have not seen this level of personalization yet in AI.

For Apple, the current focus seems to be on the reactive use cases, with significant efforts invested to allow developers to be closely integrated into Apple’s AI efforts.

Apple Intelligence Overview

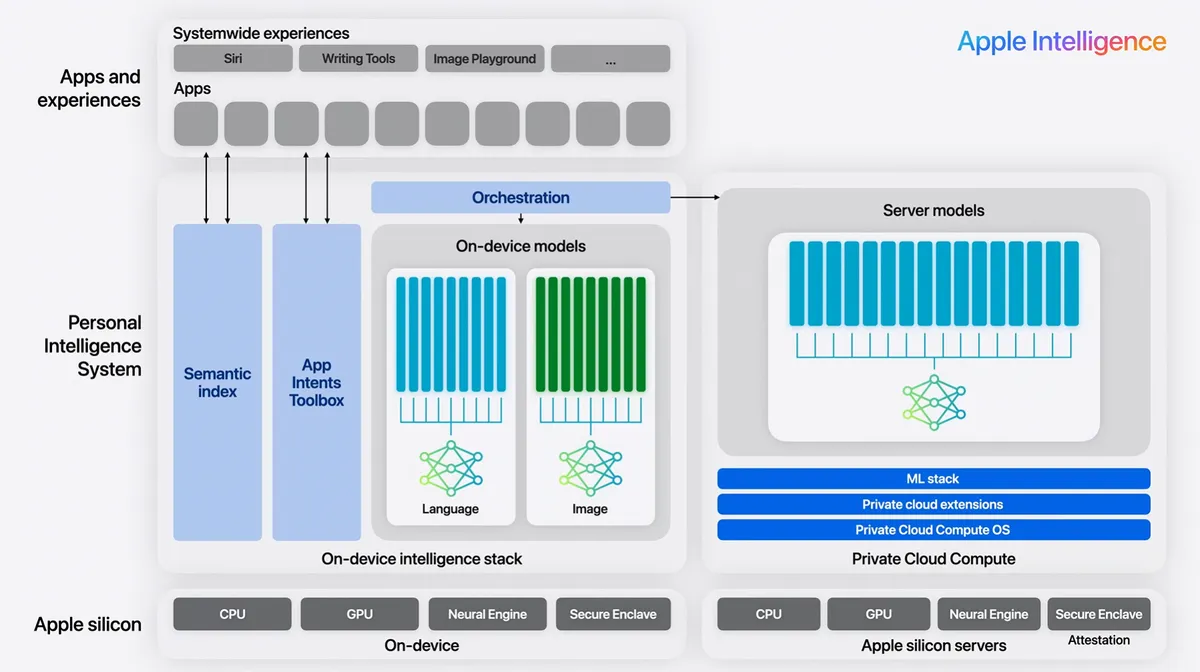

The Apple Intelligence stack is thoughtfully designed. The notable intention is that Apple’s technology stack is designed to be integrated with both 1st party and 3rd party apps.

Compute

When inference is required, the prompt, desired model, and inferencing parameters (which include guided generation methods and system instructions) are sent to the orchestrator, which decides how the inference will be processed. Besides web page summaries, which rely solely on Apple’s Private Compute Cloud, all other features appear to use either on-device or a mix of on-device and cloud models. More complicated tasks tend to be routed to the cloud model.

For Private Compute Cloud, Apple uses a cloud-based MOE model using proprietary hardware and software. This model focuses on accuracy and scalability. While the parameter count isn’t public, Apple’s Foundation Model research paper hints that it’s a similar size to Llama 4 Scout, a 109B parameter MOE model that activates 17B parameters during inference. The request sent by the user is encrypted on the client side before being sent to the cloud. Apple emphasizes privacy and security.

Apple uses a custom-trained 3B parameter on-device model. It excels at text tasks like summarization, entity extraction, text understanding, refinement, short dialog, and creative content generation. Apple explicitly states that it is not designed to be a chatbot and may have limited general world knowledge. It is also not good for complex reasoning, math, or code. To make up for its performance issues, Apple uses adaptors, which are supplemental parameters that can be added to the language model. These are swapped out based on the task.

Third-party developers are able to build on top of the on-device model, enabling features like text summarization, tagging, image generation, and text generation. Apple mentions in-game dialogue generation and itinerary generation as two potential use cases for developers. Developers can even train their own adaptors. Apple provides documentation on how to use the on-device model, but not the cloud model.

Apple’s Semantic Index

Unlike Samsung, which uses a knowledge graph for personalization, Apple uses a semantic index powered by a vector database.

The semantic index organizes personal information across both 1st party and 3rd party apps. For 3rd party apps, developers can “donate” data so that it can be indexed and used by Apple’s operating system and, in turn, Apple Intelligence.

Per Craig Federighi from WWDC24: “When you make a request, Apple Intelligence uses its semantic index to identify the relevant personal data, and feeds it to the generative models so they have the personal context to best assist you. Many of these models run entirely on-device.”

The semantic index is complemented by the App Intents ToolBox, which allows developers to provide metadata on what actions their app can take and how it can be called to action, adding tool-calling capabilities for the system. Apple states that Siri will be able to suggest actions that 3rd party apps can take and even take actions in and across apps.

Despite these efforts, Apple is still early in providing a personalized AI experience. It’s still unclear what type of personalization can be done by the combination of semantic index and App Intents. However, WWDC25 provided a glimpse of what may be coming: agentic workflow.

Glimpse into Apple’s Broader AI Vision

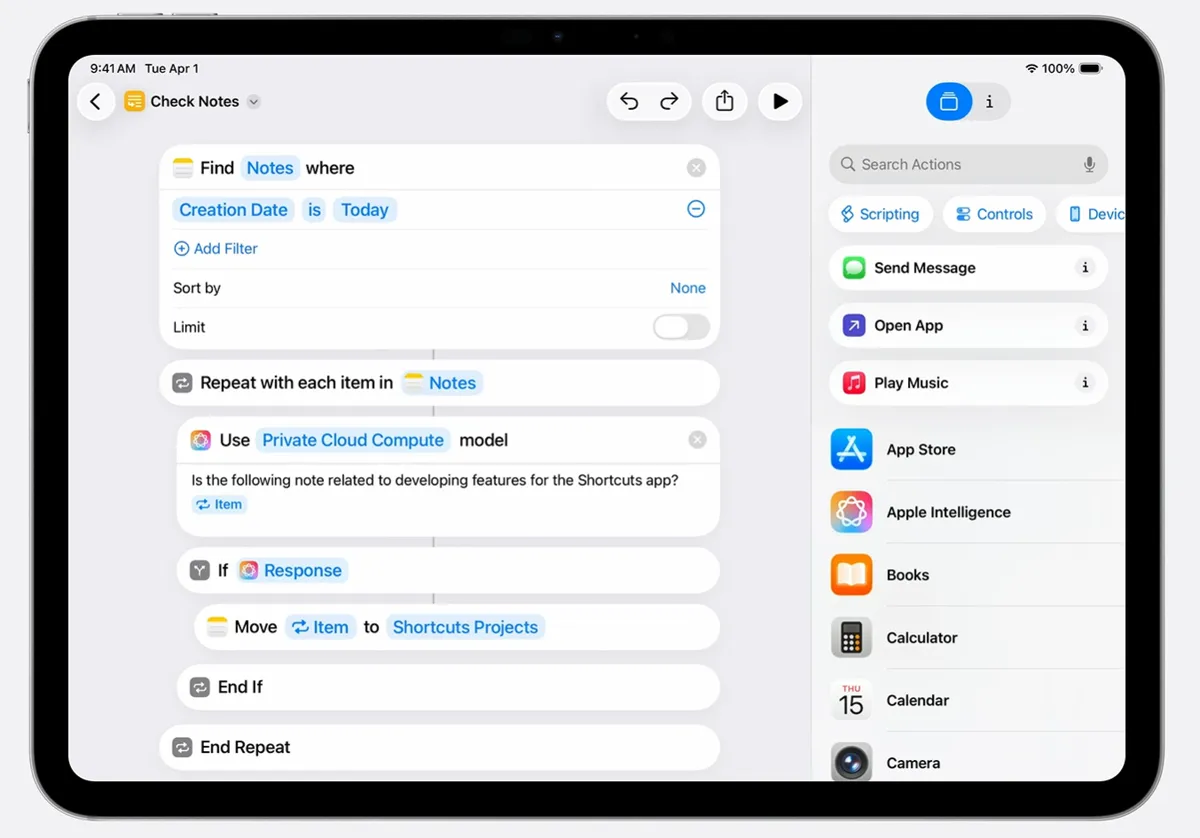

Apple’s core vision for AI is likely to be built on its Shortcuts app. Built as a hackathon project in 2014 at the University of Michigan, Workflow was acquired by Apple in 2017 and rebranded as Shortcuts. It allows users to create macros for executing tasks and automations.

At WWDC25, Apple announced the integration of Apple Intelligence into the app: “You can use Shortcuts to automate repetitive tasks and connect to other functionality from different apps. For example, to save a recipe from Safari to a note in the Notes app. This year, we’re bringing the power of Apple Intelligence into Shortcuts to make weaving these actions together easier, and even a bit more fun. With this new action, tasks that used to be tedious, like parsing text or formatting data, are now as simple as writing just a few words.”

The integration is shallow today. Rather than Apple Intelligence orchestrating the workflow itself, Apple Intelligence is incorporated as a step in the Shortcuts workflow to allow text summarization and generation using either the on-device model, Private Cloud Compute, or ChatGPT. Shortcuts still requires users to manually lay out each step of the workflow. In its current form, Shortcuts is difficult to use, and coming up with new workflows requires extensive tinkering.

From a product evolution perspective, we can expect Apple to eventually introduce a fully automated Shortcuts app that’s reminiscent of an agent. Apple has the underlying infrastructure to do so.

Barriers (and Solution) to Apple’s Agentic Product

The challenge for Apple is not simply that on-device models struggle with complex reasoning or code generation; that’s a technical limitation that will improve with time. The deeper issue is that Apple sits at the intersection of three tensions: privacy, capability, and user experience.

Consider Siri. For over a decade, it has been the archetype of a “contained assistant”: able to set timers, open apps, and answer simple queries, but incapable of orchestrating multi-step workflows. This wasn’t because Apple didn’t see the demand; rather, giving Siri the keys to the kingdom raised the question of what happens if the assistant does something unexpected. Google and Amazon leaned harder into cloud-based agents, but they paid the price in user trust, especially as stories about inadvertent recordings and data exposure surfaced. Apple made the opposite bet, limiting functionality in exchange for privacy guarantees, but that tradeoff explains the current gap.

But Apple’s history suggests it doesn’t stay constrained for long. Take hardware transitions: in 2005, the PowerPC to Intel switch was seen as nearly impossible, yet Apple reframed the narrative around performance per watt and executed flawlessly. Or look at the M-series chips: where Intel stumbled, Apple saw an opening to redefine the entire laptop experience. In both cases, the company turned a structural limitation into a differentiator. The same dynamic may emerge here.

From a privacy standpoint, Apple has already pioneered approaches that feel invisible to users but are, in fact, architectural breakthroughs. Private Relay makes your browsing look like any other CDN request, and iCloud’s end-to-end encryption ensures even Apple can’t peek. It’s not hard to imagine a future “private cloud compute” that looks and feels like on-device processing but scales up reasoning capacity in the background, bridging the gap between capability and trust.

On the hardware front, Apple controls the full stack. The A- and M-series chips are not just general-purpose processors; they include Neural Engines optimized for inference, and Apple has every incentive to continually increase local model performance. Third-party developers, from Stable Diffusion hobbyists to Llama-based app makers, will continue to push what’s possible on-device, effectively creating a testbed that Apple can later productize.

And then there’s design. Apple’s greatest advantage is its ability to take something complex—whether multitouch on the iPhone, or multitasking on the iPad—and make it feel inevitable. An agent that visibly “types” across apps would feel clunky; an agent that quietly assembles your podcast summaries in Notes, or automatically prepares your travel documents in Wallet, would feel magical. This is where Apple excels: hiding the complexity in favor of an experience that users only need to trust, not understand. Throw in the potential fold form factor, and the magic of Apple could come to a form factor only available to Android phones today.

In other words, the barriers today are the exact domains where Apple has historically redefined the problem space. The timing is uncertain, but the direction feels inevitable: the agentic Apple experience will look limited at first, but once it arrives, it will feel like the only way such a thing should ever have worked.